“An archive can be more than a massive collection of folders. It can also get involved in politics” (MONITOR, n.50, p.6, 2010).

The synthesis helps present the mission, but certainly not the entire mission of the most extensive collection on right-wing structure and ideology in Germany after national socialism. Berlin’s Antifascist Pressarchive and Education Center (Antifaschistisches Pressearchiv und Bildungszentrum Berlin e.V., APABIZ) has provided information on the extreme right since 1991, with documentation covering the period since 1945.

In partnership with the journal Biblioo I interviewed one of the persons responsible for this collection, which is part of the network of Memorial Libraries (AGGB) and is one of the most inspiring and relevant institutions I have met in Germany. Unfortunately, it is extremely topical in preserving and spreading research on a past that insists on maintaining barbarism and political violence.

This Archive is universally open to all those interested in understanding those Nazi actions and thoughts, the violence of the extreme right, meanings and consequences of neo-fascist organizations, and the spread of populist ideologies, ” Anyone who has a problem with Nazis or right-wingers and honestly wants to oppose them may take advantage from our offer” (MONITOR, n.50, p.2, 2010).

Such work involves historical retrieval, but mostly a confrontation against right-wing extremism. Based on education and quality of information and engagement in current political disputes, they prepare solid bulletins and reports (see Berliner Zustände), in addition to the educational actions of the archive and supporting friendly institutions.

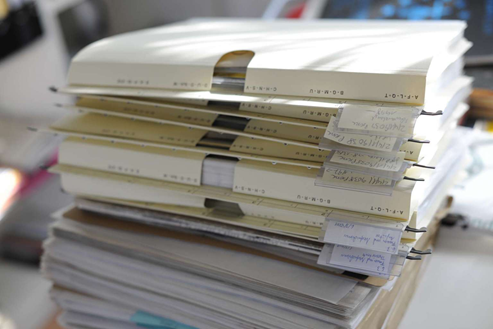

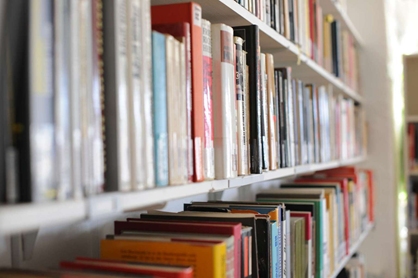

On my visit, the range and variety of this collection impressed me deeply. More than 15,000 media items ranging from brochures and books to audio, video, advertising material, textiles, and adhesives are available free of charge at the library. Its collection emphasizes primary and secondary collections, together with the archive, which provides more than 60,000 documents. More than 2,700 newspapers, duly systematized and protected behind the weighty iron door, in a building in Kreuzberg’s effervescent district.

I had a conversation with Killian Behrens because I was curious to comprehend all of the archive’s acquisitions and spreading process, which distinguishes it from conventional libraries and archives.

I went out with a somewhat bittersweet sensation. Firstly, the unpleasant side effects of knowing materials with a high burden of political violence, and all the negative impacts this brings emotionally. But at the same time, although it is an archive about “violence, murder, perpetrators and a chronology of violence and hate” (MONITOR, n.50, p.1, 2010) it is not a “place of horror” but a place to support knowledge, aiming to turn back the ideas of the extreme right. After a lively interview, I also went out with a good impression of having known incredible documentary preservation and political militancy work.

With great personal and professional enjoyment, I present to my Brazilian colleagues the work of APABIZ.

“APABIZ is an archive about Nazis, their ideology and actions. It is an archive on violence, murder, death, on perpetrators – known and unknown, and the traces left by them in the chronology of violence and hatred” (MONITOR, n.50, p.1, 2010).

I was impressed by the temporality (1945-present), mainly due to the collection of unofficial materials, easy to disperse, with demanding continuity. How is the collection of these materials and primary literature so current about extreme right?

We have materials starting since 1945, from the end of World War II. Many institutions, such as universities and other archives are working on the era of National Socialism in Germany, However, there were no massive similar scientific papers on the extreme right after 1945. Of course, those involved with National Socialism didn’t disappear after 1945, many of these people were around, and they reorganized themselves at a certain level. For example, they launched newspapers, spread their ideology, founded new political parties, and so on. As an archive, we have only existed for 30 years, so we began the documental collection in the early 1990s, which meant that most of the material we would have collected was from the late 1980s and after the 1990s.

But just less then ten years ago, we took over a massive collection from the Free University of Berlin (Freie Universitat). They were one of the few places where they had a professor researching political parties in general and collecting material on extreme right-wing political parties. And when he retired, he offered all this material to his university and his archive, which refused to acquire it because they thought it wasn’t relevant and that there wouldn’t be enough interest. This material would be thrown away at that moment. Professor already knew that we existed as an archive and asked us if we could take this collection. Which was perfect because he had material since the early 1950s. So we could just take it and put it in our archive and expand our temporal coverage.

Usually, independent archives that collect material on some social or political movement, work on movements related to their own political activity. That makes it much easier to collect because you usually know people. By living with them, you can simply ask if they are interested in sharing their material with you. We also do this on behalf of the anti-fascist movement in Germany.

As we also collect about our political movement, although our focus is on the extreme right. Because that is where the political threat comes from. And we need to be informed about what’s going on to be able to fight it. For that, we need to get the primary material, which is not simple. But on the extreme right, they have many newspapers and publishing houses where they publish their books, so these materials you can buy online.

Of course, we don’t like to spend money on this, but we still think it’s better to spend money on it and then have it here in the library so people can use it and don’t need to buy it themselves. And nowadays, many people who come here are university students who write their master’s thesis or something similar about the extreme right. They just can’t get any material in the university library because they don’t have them.

These institutions don’t collect this kind of material, which is understandable, on the one hand, but it becomes a problem when you have to do any type of research on this subject. And now, we are faced with the situation that people come here from all over the country because they can’t access this material in their universities.

We also receive pamphlets, leaflets, and everything that has been distributed in demonstrations and extreme right-wing marches, besides participating in these marches to collect material.

We also depend a lot on other people to do it, such as journalists and activists. For instance, we need to find stickers on the street, collect them on a piece of paper, and send them to us. Because we can’t be everywhere at once, but our supporters do.

And some years ago, an exhibition was held at the German History Museum, which was about extreme right-wing stickers. And this is hard to access. So they had to come right here because nobody else would collect something like that. There are some smaller archives that we work with, and they also collect these materials, but they usually have a more regional focus. For example, when they are in Bavaria, they look at the far right in Bavaria, and we look at the whole set of the German far-right.

We also receive material from investigative journalists who have been working on the issue for years. When they retire, or even they don’t want to keep this material at home, instead of throwing it away, they donate it to us, and we can make it accessible. Normally, except for newspapers and books, we can’t acquire them directly or request them. In other words, I can’t ask the NPD (National Democratic Party of Germany, ultra-nationalist and neo-Nazi matrices, banned from national politics) if they want to send me the material because they won’t do it.

How to determine which group, action, and activity will be considered extreme right to enter the collection? How does it process between selecting this information about the group/person/event and joining the collection?

This is a tough question. And there is no easy answer to it. In the early 1950s and 60s, there were many attempts to found new extreme-right parties. They usually didn’t last long. They usually only existed for a year or two or merged into other political parties and things like that. But I would say that, until the 1980s, they were like well-defined organizations.

Until the 1980s, the far right used to have a very German way of organizing with political parties, associations, book clubs, and the like. So you could say: “OK, as a diagnosis, they have activity because they still publish, for example (…)”.

And since the late ’80s and especially since the ’90s, the way of organizing has changed and became more detached. For example, I can’t simply ask, “what is this association?” it’s not possible to do that with something from this topic. Or “it’s just a group”… because they may write a name somewhere online or in a newspaper, but they may not be a group. And you can never be sure if they still exist or not.

Especially since the ’90s, we had examples that groups would organize themselves more informal, like for example comradeships. They might only exist for one or two years, and then the following year, they would need to change their name, and then their newspaper would also change its name. And this makes it very difficult for us to keep an overview. But if they didn’t publish anything for several years, you can assume that they don’t exist anymore. But it’s still hard to determine.

And, just like we do in the collection, we can engage people who are in other places. For example, I don’t know any extreme right-wing group from a small village in Bavaria that I’ve never been to. But there might be someone who is an anti-fascist there or who has some idea about how important it is to fight against the extreme right and who can call us or who can send us this material when they find it, for example, in their mailbox or anywhere.

But how do we decide if something is extreme right or not? There is a legal definition on this subject, adopted by the Secret Service and State, but it is quite restricted. So it usually takes a while for them to name someone/group as extreme-right. Commonly, we have said that some group has been on the extreme right for some years, and so have journalists. And then two or three years later, the Secret Service would say, “oh yes, we just found out that they are officially far right, from now on.”

For this reason, they can’t be the quality standard for us. There are specific definitions within the political science of what the extreme right is, and there is not just one definition, but several, although they perform similarly. Generally, it refers to ethnic nationalism. For example, a shared understanding of being German, in which you have to have German ancestry and be born here. This has changed a bit over time. Nowadays, the right doesn’t talk so much about ethnicity, but about culture. They argue, “well, this is a different culture and cultures should not mix.” This process of treating culture tangentially is because since 1945, after World War II, if you’re so openly racist, there are still people who know and say that this is not right.

And I affirm culture is something I learn by, like how I was raised, where I grew up, and what kind of values I was teached, and that can change depending on my context. And in general, culture is something that is changed every day by people. That way, if I’m raised somewhere else for example, I can grow into another culture. And they say you can’t. For example, you as someone from Brazil would have the Brazilian culture, and you could live for decades here in Germany, and for them, you will never become a German. That’s what they basically claim. In those terms, migrants could never be real Germans.

After all, it’s the same ethnic understanding about who belongs and who doesn’t. And then, this connects with different kinds of discrimination, racism, anti-Semitism, misogynistic ideas, homo- and transphobia and they may not all be explicit at the same time, or they may vary in incidence, but this essence is there.

Some groups may be stronger in the anti-Semitic aspect and not so contrary to women, or perhaps another group focusing mainly on the anti-feminist agenda. So if a group uses any of these ideologies, we would say that their material is interesting to us because we need to look at it. Maybe it’s not 100% far right. But, of course, they use this ideology, showing the connection with the extreme right.

This is particularly important for us because of the connection between the extreme right and the whole of society, so we have to look at conservatism as well. Especially now, since AfD (Alternative for Germany, extreme-right party) has this understanding of ethnic nationalism precisely. Hence, for me, they are part of the extreme right. Many other political parties feel threatened by them because they lose voters and therefore do not always oppose their agendas; they accept their demands and make them their own to gain popular support. And I think this is even more threatening because they could have more success than the AfD itself initially. So we need to look at this conservative spectrum as well.

For example, a book (“Deutschland schafft sich ab”) that has been very important to the far-right debate for the last ten years was written by a social democrat, Thilo Sarrazin. And, by definition, he and his political party don’t belong to the extreme right. But what he wrote in the book is what the extreme right is saying now as well. So we also need to look at these links with other groups and with society.

How do you handle AfD, for example, since they are in Parliament?

We say openly that we are anti-fascists, so we are noticed as a left-wing initiative. Today there are more and more people listening to us when we have to say about the extreme right, and there is an impact from us.

I’m sure the AfD observed our work, and there are always allegations that show that they’re naturally not happy with what we’re doing. They try to undermine our credibility and experience by saying that it’s all nonsense “(…) they’re the left-wing extremists. They claim that we’re not a serious institution and that people should ignore us, that we shouldn’t be funded, and we get some funding from the city of Berlin. And therefore, since the AfD is part of the parliament here in Berlin, they say that institutions like ours should not receive any funding.

They still claim that we should ignore them because they say they don’t belong to the extreme right. But this same phenomenon happens with people who adhere to this kind of idea, and they claim to be conservative.

However, even the term conservative is very vague. For example Angela Merkel is a conservative, but she leans more to the center. It is necessary for someone to be conservative, and therefore normal for someone to claim to be conservative. Although there might be things that conservatives and the extreme right have in common, there are also many things that divide them. So I think it would be beneficial if all the conservatives who don’t want to be connected to the extreme right spoke. That would help. I’m not sure if this will happen, but it would be constructive.

Apabiz is responsible for this critical work. At the same time, it brings visibility, and you can still put your work, this collection, and yourself at risk. How do you deal with possible attacks on yourself, your collaborators, and your collections?

I can mainly tell you about our collection. We have been in this neighborhood and this building specifically for the last 15 years. And in our first years, we were just around the corner, in a small corner store.

It has to do with what we can do in this central neighborhood recognized for being inhabited and frequented by an alternative left, quite diverse, and where many migrants live. We probably couldn’t do the same thing if we were in the outskirts of Berlin, which would put us in further danger, because in small villages, in the countryside, in more distant places, the extreme right scene can be quite strong. This is a massive problem for us in the last few years because we were threatened to leave this building, because the landlord wanted to sell it.. After all, it could be sold, and we could not rent this space anymore. And it is tough to find new areas in Berlin. They must be spaces where we can keep the collection safe, in a place where the far right is not strong, but not only to keep ourselves safe as an archive but as an anti-fascist group, which is doing vital research work.

And, of course, we have other security measures issues. For example, when I watch a far-right march, I’m not going to do it alone, and I like to have colleagues with me who have had experience in this for some time. So we also know what we’re getting into. And we know that we should keep a certain distance.

How do you deal with financial funding, and, at the same time, how do you deal with the issue of independence for work and research development?

Well, we would like to be completely financially independent, but this will not happen any soon. In the first ten years, I wasn’t in this job back then; we lived basically from donations. And, until today, we try to get more and more people who donate regularly. And, this way we can ensure that the collection and the space in which we are safe.

It works today. After a lot of years of campaigning, we finally managed to get to the point where we can say that we can at least afford the rent. So if all the other financial support disappears, we still don’t have to give up the area. That means as I said about prices and locations in Berlin, a lot.

But that doesn’t pay absolutely anything for our work. At some point, we had to decide, and it’s still possible to do all this voluntarily. Although this means that you have to earn your money elsewhere, and the time is limited to do what you want to do. And you probably do it with less quality because you have less time. In Germany, in the 2000s, there was considerable debate about this because state funding for initiatives like this that work against the far right was started. We decided at some point to join this local program in Berlin. There are federal initiatives, but we are not part of them.

This situation in Berlin was good because we said we are not being paid to host this Archive. This is not what they pay us for. When writing a project, a public announcement, we have to indicate what we are being paid for, what we want to do, what we should be financed for. We demonstrate that it is essential that there is an analysis of the extreme right now, what is happening in the extreme right demonstrations, who is going to this kind of event, and why.

In this regard, we are also talking about publications. We write texts, articles, bulletins, and this is super important work. We give groups that act with counseling, like mobile councils, or other agents that need a space to publish their analyses, because they have critical and valuable perspectives. We argued this way and were funded because the Senate of Berlin understood that this was necessary and we also got positive feedback so far.

And most importantly, they never tried to detain us, censor us, or anything like that. Until now, we’ve always been able to say whatever we wanted so that we could criticize whoever we wanted. If we say there’s a problem with racism within the police, they never said, “you can’t say that.” So that was important.

If they had said that at some point, we would have left the program because that’s the most important thing for us. So we need to be able to present our analysis. And they may not like it, but we still have to be able to say it. And so far, this has worked well. But as I also said before, AfD, for example, is in parliament today, and they are trying to close programs that foster these initiatives.

Thus, for us, it is increasingly important not to depend on these programs no longer. We still think it is essential that they exist and that they finance our employment at this time. And we have volunteers, not everyone who works here is in a paid position. But you know that when you start something like this job, you’ll start small, and you’ll also rely on volunteer bonds, which donate your overtime to this kind of initiative. Ideally, we would only live on donations for the future, and we would only have enough donors who would finance us every month so that we can continue doing what we are doing.

Luckily, after more than three years of fighting for this, this house here, now we can buy the house with all the other tenants of the building, and if we have to pay some amount, that is between ourselves, the tenants.This is also like a massive relief for the security of this project in the future.

Thinking about Brazil, I can say that the extreme right acts and has a strong adherence among Internet audiences. Apabiz’s focus seems to be on printed copy files. Do you do any kind of restoration and preservation of on-line materials?

Well, I think every archive needs to think about what it will do with the Internet. It’s a problem for each archive; it’s something everyone has to deal with. And mostly because social media exists, and they make this accumulation even more difficult.

In the past, if we used to follow certain websites, it was basically possible to make a list and follow “the 200 most important websites in Germany”. You could download them and save them, before that it was possible. But with social media, we basically lost that ability and not archive ourselves, but we also don’t have enough velocity required immediately to analyze, index, and organize these contents. Because if you store something, you have to make sure you find it again. And I can’t do that when I download a million Twitter accounts, for example. That won’t work.

But obviously, we look at these phenomena, and we use some content from this source for our analysis when we write articles. But, it’s tough to put digital material on file. It’s a global problem, and we believe we’re all waiting for some kind of technical solution where we can then say, OK, we’re not going to download everything yet. These are the most critical channels we need to monitor and then have a proper technical solution.

However, I find it quite interesting that, in general, newspapers go through a challenging moment. But when we look to the extreme right in the last ten years, they are starting new newspapers, and they seem to have a lot of success with this. It’s not only online, but they also managed in some way to sell their books, their newspapers, maybe not to the general public, but to the people who are willing to buy these things. And in this, they are consistent. This way, it is possible to measure that there is a market for it. Definitely, and they seem to do very well financially now.

Apabiz is also part of AGGB. In your opinion, what is the importance of being part of a professional network and, besides AGGB, in which other networks is the Archive connected?

We belong to several networks. I think AGGB and the Archive von Unten, a network of similar archives, especially ones that work mainly with social movements. And they are independents like us.

You have to organize with others to share your experience and to share your knowledge.

For example, you can learn how to work as an archivist, but many archives have no one with this technical knowledge. Either they do it only part-time, or they are not paid and have restricted time to work. So, to reach a certain level of professionalism, I think it’s imperative that we have these networks and that we can say to each other, “hey, we have, this new software that we are, you can use it too because it’s super easy and makes your life better.”

Or someone to explain to you how you could organize your books on the shelves because then they would last much longer. There are distinct networks that can give us different information, like specialized libraries, art archives, and those focusing on the extreme right theme and analyzing it. This variety is excellent for us since we also want to do educational work, and it’s always good to benefit from all this possibility of knowledge exchange.

For example, a project that we are hosting here. For instance, we are part of the NSU Watch (NSU Observatory). This project was founded to monitor NSU, the National Socialist Underground (National Socialist Underground Movement, a terrorist group of the extreme right, responsible for 10 murders, several bomb attacks, robberies). The lawsuit was held in Munich, and then different committees of inquiry and local parliaments took place. To observe the trail we could not have done from Berlin. So we met with people from other parts of Germany who then investigated this in their region. And as a network we monitored the trail and the committees of inquiry. We shared how to deal with the extreme right on a national level and supported ourselves in this complicated case, which is still in big parts unsolved today.

And since you can’t get all knowledge about everything, the extreme right is scattered in many different places and so many other groups, with very different focuses and various nuances. Therefore, we need people to help us, even at an international level. And Germany is always exciting for people who investigate the far right and fascism, even though we know that it is as if there is also a global return now. You have countries on the far right, and in some of them, they run the government. You come from Brazil, and you know what I’m talking about.

For example, in recent years, when we’ve been talking to people from Italy, it’s a massive difference in the periods when the extreme right is in opposition, or on the rise, or whether they run the government.

And at that moment, you can look at Italy or Austria and see how society is changing. And that can help us to deal with what might be coming in Germany as well and then fight against it, with networks of support and sharing.

I read an important statement about Apabiz in an interview, “You don’t come here just to see terrible things.” At the same time, it’s impressive to see this work here, but it’s also bittersweet because this work is essential until today.

I don’t know how certain it has changed, but certainly, some things have become more visible. Some decades ago, it was challenging to talk about racism in Germany. And it still is, but there is more awareness today, I think.

And almost everyone can agree, that facism is something to be opposed. Even the modern far-right now doesn’t want to have anything to do with fascism anymore. We don’t need to believe that, but that’s what they are saying. And that means that they can’t just say these things openly, and that’s because they don’t feel safe enough yet, which is a good thing.

On the other hand, not everyone calls themselves antifascist. because the word antifascism in Germany has a very negative imprint to some people. But it is essential to understand that, in the end, facism is a threat to everyone who wants to live in a democracy, so it should be opposed by all of us.

For example, now with the Black Lives Matter movement, people always say: it’s not as bad as in the United States. That might be the case, but we also have colossal police brutality. For example, no case study has been done in Germany on police violence and racism within the police for decades.

But some politicians still say that we don’t even have to look at it, because here in Germany it’s not like that. So they deny the problem immediately. And that’s very frustrating.

But on the other hand, there are moments when I see that the resistance also works. Today, I can – it’s quite challenging to be positive, especially with everything we see politically – I can only talk about Germany, but if you look at how things have changed in the last 30, 40 years, we’ve seen, for example, more rights of the LGBTIQ community, or that not even 30 years ago, it would not be possible for you as someone who was born somewhere else to be considered a German. So I see that this has changed at some point, but very slowly.

We could have been much quicker with this, but now it’s probably still more comfortable to live in Germany than it was 40 years ago, so sometimes I am also hopefull.